Levan Gabriadze is a film and theater director who currently oversees the artistic operations of the renowned Rezo Gabriadze Marionette Theater in Tbilisi, Georgia, a venue founded by his father, a celebrated playwright, screenwriter and theater director.

In film, Levan Gabriadze is best known for Unfriended (2014), a landmark for both digital horror cinema and screenlife, as its entire narrative unfolds in real-time, on a computer screen. By confining all action to a laptop interface and using everyday applications such as Skype and Facebook as key storytelling devices, Gabriadze immersed audiences in an unsettlingly familiar digital space. The film tapped into modern anxieties regarding cyberbullying and online privacy, paving the way for subsequent screenlife projects.

This interview will focus mainly on the film’s production process, its legacy and how it addresses themes related to digital horror and technological interfaces.

Tiago Ramos – In Unfriended (2014), the true source of horror isn’t the ghost that seeks revenge, but rather our anxieties concerning digital media. The medium is the monster. Do you believe that, on an infrastructural level, digital devices and internet-mediated platforms predispose people to act monstrously, insofar as they encourage more reactive responses, using algorithms that favor content that generates violent interactions?

Levan Gabriadze – The crux of the issue is in the unique environment of cyberspace, which fosters a degree of anonymity and detachment absent in face-to-face interactions. This phenomenon, similar to the road rage experienced within the confines of a car, allows individuals to bypass the moral foundations – rooted in upbringing and education – that typically guide their behavior in the physical world. Ultimately, the internet is a tool. The responsibility falls not on the technology itself, but on our capacity to remain faithful to the principles that guide our lives. The challenge for modern parenting and education is to instill these principles early, ensuring that children understand they must behave in online spaces with the same accountability as in the real world.

Tiago Ramos – Digital technoference, the displacement of face-to-face interaction by screen time, is a well-established feature of modern life. If the average person’s daily screen time now exceeds their time spent in school or in direct social contact with friends and family, does that mean that the sheer volume of media exposure renders even the most attentive education secondary to the influence of digital platforms?

Levan Gabriadze – Managing children’s media exposure is a daily challenge. In many ways, it feels like a losing battle. Over the last decade, the film’s subject and the problems it addresses have become more daunting.

Tiago Ramos – If a film with a similar concept were produced today, how would it be different? What new themes, such as artificial intelligence, would be incorporated, and what cinematic techniques would be used?

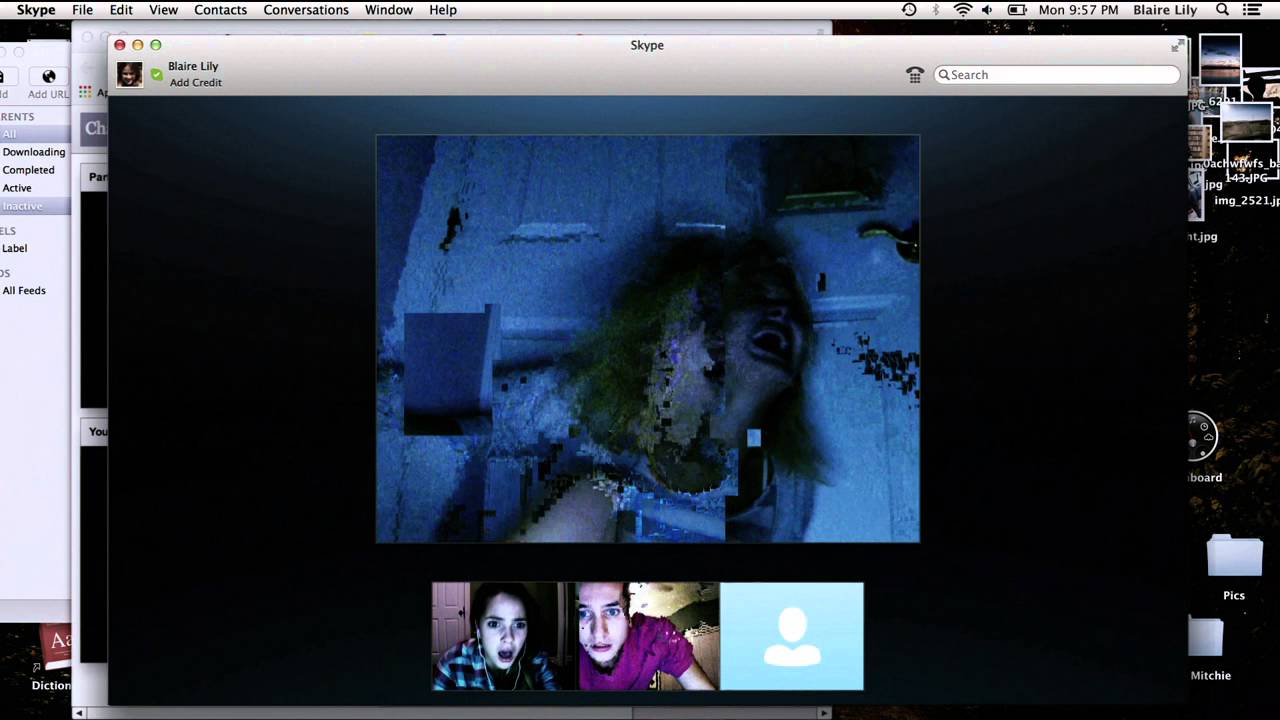

Unfriended (Levan Gabriadze, 2014)

Levan Gabriadze – A contemporary reimagining would require a deeper dive into artificial intelligence and the mechanics of psychological subversion. Today, manipulation has become incredibly sophisticated, largely due to AI’s ability to distort individual worldviews and erode our shared sense of reality. Timur Bekmambetov is the person to consult on these matters. He came up with the idea for this film. He has spent the last decade immersed in this sphere, particularly within the horror genre. For me, however, that project was a one-time exploration. Through it, I discovered that my creative sensibilities do not align with horror. My perspective was shaped by my upbringing in the Soviet Union, where horror cinema simply didn’t exist as a cultural staple. The idea of going to the movies specifically to be scared was foreign to me. Filmmaking is an immersive commitment – in this case, I devoted two years of my life to the project, during which my wife, Veronika Gabriadze, who also worked on the film, was pregnant. I realized I didn’t want to spend my days calculating how to trigger fear in others. It isn’t in my character. Since then, I have returned to the theater, where our work often strives for the exact opposite of terror. In a world that is already frightening enough, I no longer find it artistically compelling to add to that fear.

Tiago Ramos – Naturally, it is easier to express digital horror through cinema rather than theater, given that there’s a stronger affinity between cinema’s technologies and digital media. Since 2014, our reliance on digital devices has intensified. We are no longer just users, but subjects captured by the interface. One of the film’s most haunting images is that of teenagers physically and metaphorically trapped within their own digital frames, unable to close their laptops or escape the screen’s glow. This perfectly encapsulates the contemporary condition of media capture. To what extent does this systematic tracking of our gestures, movements and attention resonate with you, and do you find the implications of this entrapment fundamentally horrifying?

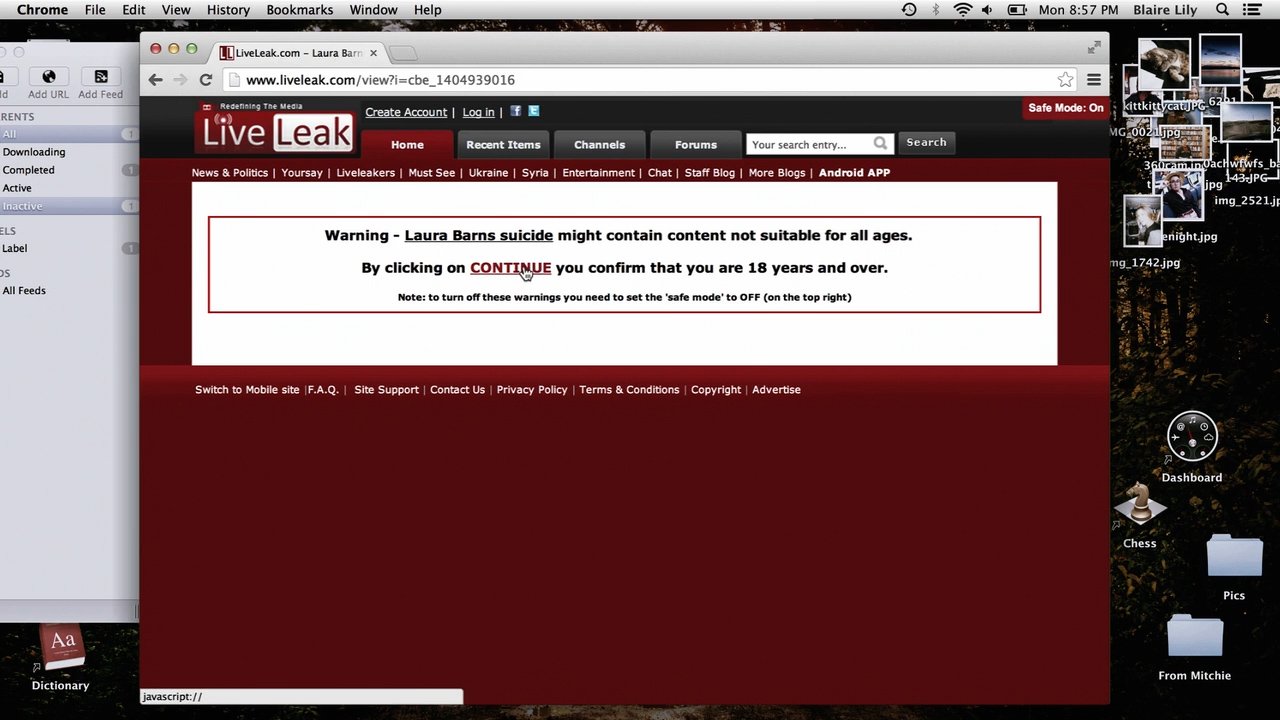

Levan Gabriadze – As a director, I am in the business of capturing attention. Whether in theater or cinema, the objective is to captivate the audience, to induce a dreamlike state wherein they transcend their daily lives and immerse themselves in the journey of our protagonists. From that perspective, losing the audience is the ultimate failure. I understand the mechanics of engagement, which allows me to recognize how social media platforms and AI companies employ similar tactics, albeit for very different ends. In theater, attention is sustained through dramatic structure – it is a long-form emotional journey in which the audience becomes invested in the resolution of the narrative. Today, however, those journeys have been fragmented into ten-second micro-cycles. We have moved away from cohesive storytelling toward a digital kaleidoscope of rapid-fire information. While much of this content can be interesting, the medium’s velocity ensures that it is forgotten as quickly as it is consumed. We are being fed a wealth of information that we are unable to retain. Timur Bekmambetov’s core vision was to render the mundane extraordinary. How do we transform a standard computer desktop into a source of tension? Your computer is the ultimate confidant – it possesses a more intimate knowledge of your psyche, your secrets, and your history than even your closest relatives. This makes the digital space a site of extreme vulnerability. If an external force accesses your passwords or your files, the potential for damage is immense. By using the screen-life format, the computer screen ceases to be a tool and begins to feel like a living, predatory entity. It isn’t a haunted appliance, like a rogue vacuum cleaner. This is the subversion of your diary and your very life. The horror lies in the realization that the tools we rely on to navigate the world can so easily be turned against us.

Unfriended (Levan Gabriadze, 2014)

Tiago Ramos – The film deconstructs the illusion of digital anonymity – the false sense of invisibility we experience online when, in reality, we can be exposed. Regarding the screen-life format, cinema has historically functioned through remediation, meaning filmmakers make films intended for the movie theater while remaining mindful of the eventual transition to television broadcasting, streaming or physical media. Although Unfriended was a significant theatrical success, many critics argue that it’s best experienced on a laptop, where the characters’ interface perfectly mirrors the viewers’. Do you agree that the definitive experience is watching it at home, thus blurring the line between the audience and the protagonist?

Levan Gabriadze – Absolutely. The film is best enjoyed at home, late at night, in total darkness. That setting heightens the emotional stakes. From its inception, the film was designed for the laptop screen. While Universal Pictures distributed the film to a global theatrical audience, we originally intended to release it on YouTube as an experimental film.

Tiago Ramos – Are you surprised that the film has been discussed outside of horror movie fandom? It has been the subject of academic essays, books and conference discussions – perhaps because it is experimental. Does it surprise you that this horror movie has become a subject of study at universities?

Levan Gabriadze – It is a pleasant surprise. The horror genre has always been a fertile ground for experimentation, largely because the lower production costs allow for greater risk-taking. Take The Blair Witch Project (Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez, 1999), for example. It was a watershed moment that terrified audiences by using the aesthetics of the handheld camcorder. That film effectively birthed the found footage movement. Our project is an evolution of that lineage – it is, in essence, found footage for the digital age, relocated to the desktop.

Tiago Ramos – So you were aware that Unfriended would be engaging with the legacy of found footage cinema?

Levan Gabriadze – Most definitely. That genre revolutionized filmmaking by showing young directors that they could make movies without a massive budget. Another reference was Mike Figgis’s Timecode (2000), which unfolds like a play. Structurally, I viewed Unfriended as a play. The narrative moves forward in real-time, sustained by a single take, without traditional cuts, much like a stage performance. The challenge, however, is that scripted dialogue often sounds too polished for the found footage aesthetic. In real life, conversation is messier. To bridge this gap, we adopted a unique process. After casting, we moved the actors into a house, networked their computers, and began a rehearsal period. Eventually, I took the scripts away entirely to force the dialogue to become more natural and spontaneous. A key strategic move was hiring two stand-up comedians. Their improvisational instincts were important. We spent a couple of weeks rehearsing the entire story as a live performance, running the full play two or three times a day. Then, we reviewed the daily footage, treating it as a laboratory, asking ourselves: What if we pushed the narrative in this direction, or explored that specific tension? However, the real work began in the editing room. Post-production was a dense undertaking due to the sheer volume of digital layers required. Our editors, Parker Laramie and Andrew Wesman did a lot of the heavy lifting. Every interaction on the desktop, from the cursor’s path to the notifications’ timing, had to be animated by hand. Today, Timur B. has developed software to streamline this screen-life workflow, but at the time, we built it all from scratch. Technologically, it is a remarkably layered piece.

Tiago Ramos – Your description highlights the profoundly intermedial nature of the production. It was staged like a theater play, yet it exists as a film, one that crosses the boundary into digital media by using the computer screen as its primary canvas. A fundamental element of mise-en-scène is the strategic organization and display of information. This film required you to present a great deal of data simultaneously, filtered through the specific aesthetics of a computer interface.

Levan Gabriadze – We had to synchronize six different live feeds so that, when a joke was told, every reaction shot landed in perfect unison. This digital choreography was complex, which is why we rehearsed so extensively.

Tiago Ramos – I imagine the challenge was twofold: keeping the actors in sync while ensuring precise interaction with the interface.

Levan Gabriadze – It was synchronization hell.

Unfriended (Levan Gabriadze, 2014)

Tiago Ramos – One curious aspect of the film is that its reality effect relies more on the authenticity of the interface interactions than on the actors’ footage. This suggests that our contemporary sense of reality is inextricably linked to our virtual lives. In a sense, you directed a stage play, but the actual image composition was an act of post-production assembly. Do you feel that organizing information within the frame in this way is closer to user interface design than traditional cinematography? For instance, the film creates digital depth of field by overlapping windows and tabs, a principle rooted in interface architecture rather than optics.

Levan Gabriadze – The actors’ footage provides the dialogue, but the action takes place on the desktop. This was Timur’s concept, and he and Nelson Greaves, our producer, oversaw the film’s development. We deliberately shifted the dramatic weight away from the video feed and onto the desktop itself. Our goal was to ensure that the primary narrative interest was generated by the digital environment, not the actors’ faces. Regarding the relationship between the composition and user interface design, consider a traditional chase scene: you can portray someone running through the woods, but you can also simulate a chase through the frantic rhythm of typing or the opening of navigation folders. We brought suspense to the desktop through software crashes, system errors, and windows spiraling out of control. The objective was to demonstrate that life on a desktop can be just as dramatic, and just as capable of sustaining a feature-length narrative, as any physical space.

Tiago Ramos – The film uses the specific traits of its medium, such as glitches, intrusive pop-ups and audio distortion, to induce fear. How central was it to use these inherent digital artifacts to create a sense of horror?

Levan Gabriadze – It was vital. When your narrative is confined to a desktop, your toolkit is inherently limited. Those annoying pop-ups and system glitches were important because there were few other strategies available. The experimental heart of this process was learning how to navigate those constraints, turning technical limitations into opportunities for narrative and formal experimentation.