As an artist and activist, I often wonder about the effectiveness of my actions. Sometimes it’s clear and immediate, but more often it’s not. I patiently participate in armchair activism, clicktivism, signing online petitions and retweeting and reposting and emailing politicians and all of this endless activity that is today’s so-called activism, but the answering flow of upbeat emails telling me what a difference I have made doesn’t always ring true. Yes, we are many, and yes, our combined voices have power, and yes, we must continue to speak up and be counted; but in fact, what gives me more sense of achievement is small group conversations and micro-actions that might only affect one person – but with lasting impact. Nothing makes me feel more gratified than when, for example, someone tells me that the performance of make-shift that they participated in almost ten years ago, still resonates and makes them think more deeply about their daily actions.

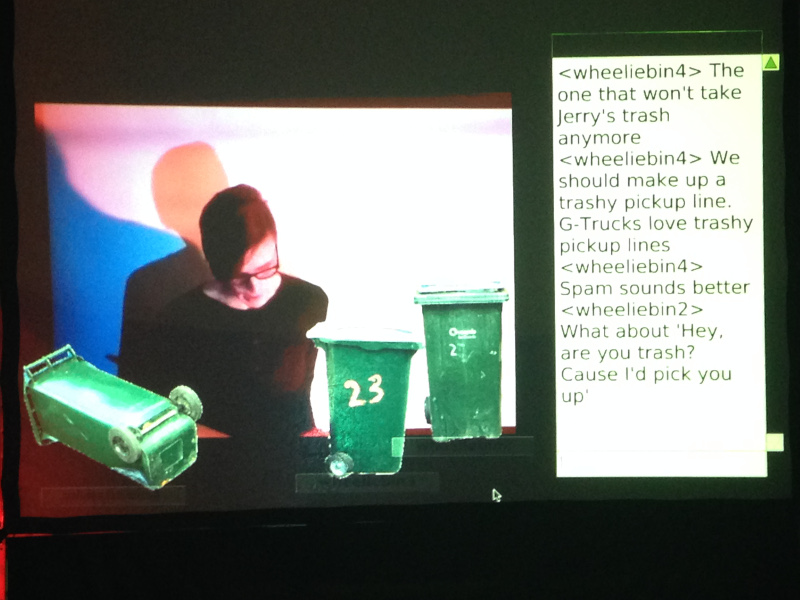

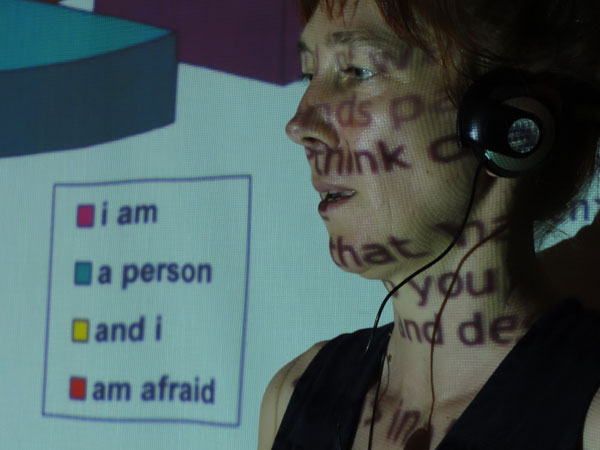

Yes, online activism is essential in these times of crises and extremism; but to achieve real change, the heady adrenaline of mass action must be accompanied by the anchor of thoughtful conversations; and this is where I feel my energies are most useful. For more than a decade, within my practice of cyberformance I have explored the potential of networked conversations as a form of net-activism. In the networked performance event make-shift (2010-12, in collaboration with Paula Crutchlow) we went into people’s homes to ignite conversations about disposability and consumption, plastic and the environment, and how our small domestic actions can have unintended consequences on the other side of the planet. In the ongoing project We Have a Situation! (since 2013) I work with local artists, activists and organizations to create global networked conversations around urgent issues such as water pollution, e-waste, industrial agriculture and community.

Foto 2 – (John Hammersley) Rehearsal for We have a situation, Coventry!, November 2016.

The Method

We have a Situation has engendered seven “situations” so far: the initial series of four in 2013, funded by the European Cultural Foundation and created in collaboration with Furtherfield (London), APO33 (Nantes), mad emergent art centre (Eindhoven) and Schaumbad Freies Atelierhaus (Graz), followed by three further “situations” created at the invitation of festivals and universities (in Rio de Janeiro, 2015, Coventry, 2016, and Newcastle, 2018). In each case, the local hosting group chose a specific issue or “situation” that was currently locally urgent, and gathered local participants, as much as possible engaging people from the community who are connected to, affected by or working with the issue. A research period, where information is gathered and shared online over several months, preceded an intensive workshop of about one week, during which a cyberformance was devised from the research material. This live performance was then presented simultaneously to a local proximal audience (in the same physical venue as the performers) and an online audience, using the online platform UpStage.

The cyberformance functioned as a provocation for a networked conversation between the performer-participants (local and sometimes also online) and the two audiences – local and online. We aimed to present different aspects of and perspectives on the situation without posing solutions, in order to open up complexities and ask difficult questions. The audience was invited to think and actively respond to the issues. As the cyberformance and ensuing discussion were mediated through digital technologies, there was an added sense of remove, distance or verfremdungseffekt for the audience that can be uncomfortable but invites the audience to look at the situation from different perspectives. The technical mediation may also help to temper emotional reactions, to see things from another person’s point of view, to re-process information that we thought we already knew thoroughly and to make new discoveries. It can be uncomfortable, confusing, challenging or even irritating, but this means that when we come to the conversation we have been shifted at least a little from our familiar, well-rehearsed opinions and as a result can engage in a different kind of conversation.

Foto 3 – (K.Hayek) The London Situation focused on electronic waste and took place in March 2013.

Local and Global

The goal of the networked conversation is to bring together the local and global, to find points of commonality in our diversity, and from there to work towards solutions that we could not have found on our own. A further goal is resonance: continuing to think about the issues after the event, initiating discussions with friends and family who were not at the event, paying attention to the issue and making small personal changes in one’s daily life.

Networked conversations between local / proximal and global / online audiences are difficult to facilitate. Leaving aside the inevitable technical disruptions (there always is something that goes wrong!), there’s the simple fact of the priority of the proximal. The immediacy of the people in the room is always stronger than the words, voices and images of the remote participants that are received through screens and speakers. The people who are physically in the same space respond to each others’ body language, talk over or interrupt each other, and create energy within the group that is difficult to share with those online. The online participants often experience lag, disconnections and other technical interference which can result in their responses appearing long after the proximal group has moved on in the discussion. Strategies that I have explored to mitigate this imbalance include having a dedicated person in the proximal space who is responsible for inserting the remote participants’ voices into the discussion; and using the “fishbowl” discussion method. In this method, four chairs are placed in the centre of a circle of chairs, and whoever wants to speak takes a seat in one of these four chairs. Only those sitting in the four centre chairs can speak, and they speak just to each other, not to the whole group. Those in the outer circle listen, as if eavesdropping on a conversation at a cafe table. When someone leaves one of the four chairs, another person from the outer circle can join. (Interestingly, I have found that participants are generally very good at changing places – they recognize when they have been there long enough or that someone in the outer circle needs a turn, and voluntarily vacate the chair they have occupied. Only occasionally have I had to tap someone on the shoulder and suggest they give someone else a turn.)

In the networked conversation variation of the fishbowl method, the dedicated person responsible for assisting the online voices to be heard always has a seat in the centre, since they are attempting to represent many voices. This is not an easy role: they need to multi-task, following both the proximal discussion and the online text chat, which can be very random and disrupted. They need to be a fast typist, a focused thinker, perhaps with multiple languages, and with a clear voice. They also need to be able to voice the opinions of others even if they do not agree with them, which is another interesting challenge in the mediation of the conversation. The online audience sometimes develops a separate online conversation within the text chat that follows a very different direction to the proximal conversation – not a bad thing in itself, but an additional challenge for the mediator between the two worlds.

I cannot say that I have succeeded in finding the best way to facilitate these networked conversations. There is usually a degree of rupture and fragmentation for both proximal and online participants. But what I have found is that people rarely give up and leave, even those who may be struggling with a disrupted connection or technical difficulties. As long as there is someone working to maintain communication between the proximal and online spaces, there is a sense of shared engagement in the process. Perhaps because of the technical mediation, which for many people is still something novel in a live performance audience situation, the audience’s experience of both the cyberformance and the networked conversation is more focused and profound.

Foto 4 – (Renato Mangolin, Multicidade Festival) In Rio de Janeiro before the Olympiads, We Have a Situation, focusing on water pollution, questioned the water quality of Guanabara Bay where some of the sports took place.

Conclusion

To return to my opening musings about the effectiveness of my activism, I refuse to play a numbers game or to define “success” on any tangible outcomes. Rather, the significant and lasting personal impacts experienced by audiences and participants are the results that I value. Feedback received over the last decade indicates that the proto-political engagement and awareness-raising achieved through the combination of cyberformance and networked conversation translates into a variety of direct actions along the continuum from personal (changes in daily habits) to political (activism). As we collectively grapple with the impacts of digital technology amid the collapse of both capitalism and democracy, opportunities for critical thinking and the development of new forms of citizen engagement are ever more essential. Projects such as make-shift and We have a situation! create an accessible, participatory space away from the commodified comfort zone of social media, “clicktivism” and consumption, in which participants can engage in meaningful discussion and plant the seeds of proto-political engagement and post-democratic activism.

Foto 5 – (Suzon Fuks) make-shift in Brisbane, 2012.